The Teleological Argument for the Existence of God

Perhaps the oldest and most popular of all for the existence of God is the teleological argument. It is the famous argument from design. It infers an intelligent designer of the universe just as we infer an intelligent designer for any product in which we discern evidence of purposeful adaptation of means to some end (telos).

Biblically, the roots of the teleological argument may be found in the creation narrative in Genesis, where the different parts of creation serve a purpose in the overall plan of God’s universe. The philosophical difficulty is knowing whether (or to what extent) it can be said that this purpose is intrinsically necessary, or whether it is merely accidental, determined by an essentially random process and not by a preordained divine plan.

In biblical times, this problem did not arise because everybody agreed that there was a divine mind behind the order of creation. Psalm 19 and Jeremiah 33:20-35 both emphasize what we would now call the laws of nature and tie them in very closely to God’s preordained vision for his chosen people. As long as biblical theism could be taken more or less for granted, the validity of the teleological argument was accepted as a matter of course, and little was said about it.

Plato and Aristotle

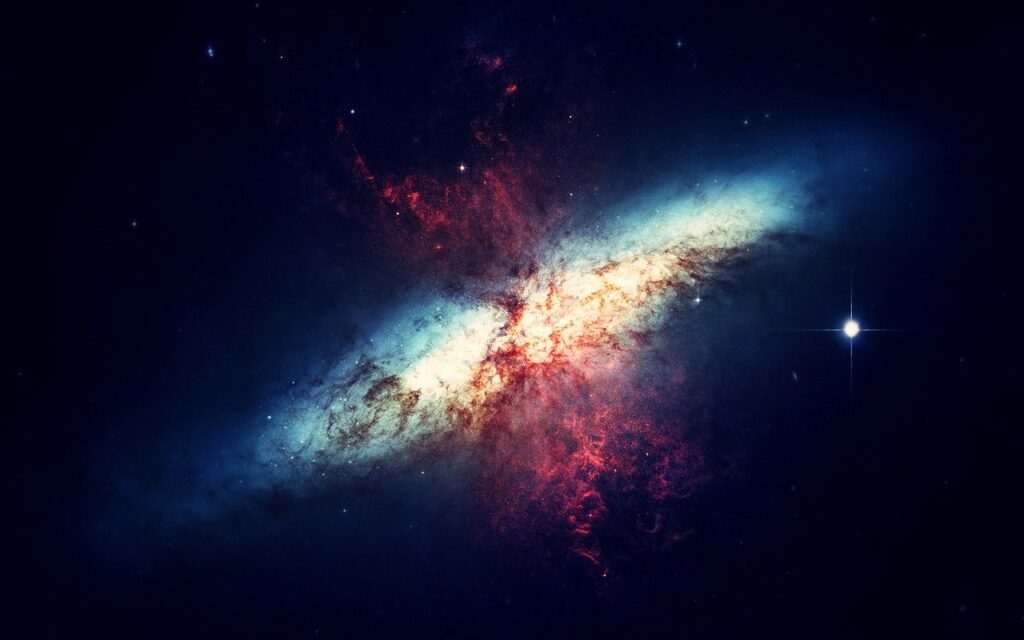

The ancient Greek philosophers were impressed with the order that pervades the cosmos, and many of them ascribed that order to the work of an intelligent mind who fashioned the universe. The heavens in constant revolution across the sky were especially awesome to the ancients.

Plato’s Academy lavished extensive time and thought on the study of astronomy because, Plato believed, it was the science that would awaken man to his divine destiny. According to Plato, there are two things that “lead men to believe in the gods”: (1) The argument based on the soul, and (2) the argument “from the order of the motion of the stars, and of all things under the dominion of the mind which ordered the universe.” Plato employed both of these arguments to refute atheism and concluded that there must be a “best soul” who is the “maker and father of all,” the “King,” who ordered the primordial chaos into the rational cosmos were observe today.

An even more magnificent statement of divine teleology is to be found in a fragment of a lost work of Aristotle entitled On Philosophy. Aristotle, too, was struck with wonder by the majestic sweep of the glittering host across the night sky of ancient Greece. Philosophy, he said, begins with this sense of wonder about the world: “For it is owing to their wonder that men both now begin and at first began to philosophize; they wondered originally at the obvious difficulties, then advanced little by little and stated difficulties about greater matters, e.g., about the phenomena of the moon and those of the sun, and about the stars and about the genesis of the universe.”

Aristotle concluded that the cause of the universe was divine intelligence. He imagined the impact that the sight of the world would have on a race of men who had lived underground and never beheld the sky:

When thus they would suddenly gain sight of the earth, seas, and the sky; when they should come to know the grandeur of the clouds and the might of the winds; when they should behold the sun and should learn its grandeur and beauty as well as its power to cause the day by shedding light over the sky; and again, when the night had darkened the lands and they should behold the whole of the sky spangled and adorned with stars; and when they should see the changing lights of the moon as it waxes and wanes, and the risings and settings of all these celestial bodies, their courses fixed and changeless throughout all eternity—when they should behold all these things, most certainly they would have judged both that there exist gods and that all these marvelous works are the handiwork of the gods.

In his Metaphysics Aristotle proceeded to argue that there must be a First Unmoved which is God, a living, intelligent, incorporeal, eternal, and most good Being who is the source of order in the cosmos.

Hence, from the earliest times men, wholly removed from biblical revelation, have concluded on the basis of design in the universe that a divine mind must exist.

Thomas Aquinas

We’ve already seen that Thomas Aquinas in his first three Ways argued for the existence of God via the cosmological argument. His Fifth Way, however, represents the teleological argument.

He notes that we observe in nature that all things operate toward some end, even when those things lack consciousness. For their operation hardly ever varies and practically always turns out well, which shows that they really do tend toward a goal and do not hit upon it merely by accident. Thomas is here expressing the conviction that everything that has not only a productive cause but also a final cause or goal toward which it is drawn.

For example, poppy seeds always grow into poppies and accords into oaks. Now nothing, Aquinas reasons, that lacks consciousness tends toward a goal unless it is under the direction of someone with consciousness and intelligence. For example, the arrow does not tend toward the bull’s eye unless it is aimed by the archer. Therefore, everything in nature must be directed toward its goal by someone with intelligence, and this we call “God.”

William Paley

Undoubtedly, the high point in the development of the teleological argument came with William Paley’s brilliant formulation in his Natural Theology in 1804. Paley combed the sciences of his time for evidences of design in nature and produced a staggering catalogue of such evidences, based, for example, on the order evident in bones, muscles, blood vessels, comparative anatomy, and particular organs throughout the animal and plant kingdoms.

So conclusive was Paley’s evidence that Leslie Stephen in his History of English Thought in the Eighteenth Century remarked that “if there were no hidden flaw in the reasoning, it would be impossible to understand, not only how any should resist, but how anyone should ever have overlooked the demonstration.”

Paley’s chief argument was that of a blind “watch-maker.” Paley’s argument runs like this:

- You’ve never seen a watch and you don’t know what a watch is for or all about.

- You stumble in the forest and find a watch. Immediately, we know what a watch is and that it has a purpose and a designer.

- Paley wrote: “The inference, we think is inevitable; that the watch must have had a maker; that there must have existed, at some time, and at some place or other, an artificer or artificers, who formed it for the purpose which we find it actually to answer; who comprehended its construction, and designed its use.”

This conclusion, Paley argued, would not be weakened if I had never actually seen a watch being made nor knew how to make one. For we recognize the remains of ancient art as the products of intelligent design without having every seen such things made, and we know the products of modern manufacture are the result of intelligence even though we may have no inkling how they are produced. Nor would our conclusion be invalidated if the watch sometimes went wrong. The purpose of the mechanism would be evident even if the machine did not function perfectly. Nor would the argument become uncertain if we were to discover some parts in the mechanism that did not seem to have any purpose, for this would not negate the purposeful design in the other parts. Nor would anyone in his right mind think that the existence of the watch was accounted for by the consideration that it was one out of many possible configurations of matter and that some possible configuration had to existent in the place where the watch was found. Nor is it enough to say the watch was produced from another watch before it and that one from yet a prior watch, and so forth to infinity. For the design is still unaccounted for. Each machine in the infinite series evidences the same design, and it is irrelevant whether one has ten, a thousand, or an infinite number of such machines—a designer is still needed.

Now the point of the analogy of the watch is just this: Just as we infer a watchmaker as the designer of the watch, so ought we to infer an intelligent designer of the universe.

David Hume

The main opponent of the traditional teleological argument was David Hume who produced five arguments against it, some of which are still used today.

One: Hume argued that even if it could be demonstrated that the world was created according to a prearranged design, it was not at all clear what caused the designer to come into existence.

Two: He also said that there is no reason why such a designer (if one exists) should correspond to the God of the Bible, because there was no intrinsic need for a designer to be perfect, omniscient, or loving.

Three: There might even turn out to be more than one designer, a theory which might make it easier to explain conflicts caused by the existence of evil, for example. In Hume’s mind, the existence of evil was proof that if there were a single designer, he could not be morally perfect, and on those grounds the biblical God was excluded from consideration.

Four: Hume rejected the use of analogies taken from the created order which are meant to show that the universe as a whole follows the same principles. It is one thing to say that the existence of a machine demands the supposition that an intelligent being created it, but this cannot be projected onto the universe because whilst there are many machines (which can be compared to one another) there is only one universe (which is therefore incomparable to anything else).

Five: Hume claimed that any coherent universe will appear to be designed as such by those who live in it, because they lack the perspective needed to imagine anything else.

Of all these arguments against design, the strongest is that the supposed designer does not have to be the Christian God. There is no doubt that the God of the Bible has many characteristics which are not necessary in a designer (e.g., love). Anyone who believes in the God of the Bible will be obligated to attribute the design of the universe to his all-knowing mind.

Charles Darwin

Paley came after Hume and Paley’s arguments largely “won the day” until 1859 when Charles Darwin published his theories of evolution and undercut Paley’s arguments dramatically. Darwin believed in random genetic change and in natural selection, two processes which made it possible for higher forms of life to emerge out of lower ones.

These mechanisms of the universe were not, therefore, an eternal given but rather an evolving process where chance was more important than design. The order and regularity of the universe as we see it could be attributed to the process of attrition which evolution involves, rather than to some foreordained divine plan.

At the time, many people accepted the force of Darwin’s arguments and support for Paley faded away. But if the older form of the teleological argument was no longer as strong as it had been previously, the essential premises of that argument remained valid. For one thing, there was still the problem of the inorganic world, which was not subject to evolution, and yet which seemed to be perfectly designed to support life.

F. R. Tennant and Richard Swinburne are two theologians who took up the cause of defending the teleological argument in the face of Darwinism. Tennant moved away from the approach taken by Paley to a time-based framework which stresses regularity of succession. According to this way of thinking, the fact that actions can be predicted with complete accuracy once the appropriate gives are known disproves the theory of purely random change and supports the idea that there is a mind governing the observed pattern. In the end Tennant claims the teleological argument comes out stronger for having faced the challenge of Darwinism and adapted itself accordingly.

Swinburne also mentions the argument from beauty, which has seldom been put forth in recent years. To some extent, beauty is a subjective measurement. However, there can be no doubt that people everywhere have found great beauty in the order of the universe, which makes it seem strange to deny the real existence of a coordinated harmony on which such notions of beauty are generally based.

This Bible class was originally taught by Dr. Justin Imel, Sr., at Church of Christ Deer Park in Deer Park, Texas.